Enabling Constraints

A post about the origins of this Substack

Oliver Burkeman is one of my favorite authors because he has an uncanny ability to describe aspects of my lived experience that I’ve never been able to articulate.

A quote from one of his blog posts, “What if you’re already on top of things?”:

Apparently I struck a chord on Twitter the other day when I observed that many people (by which I meant me) seem to feel as if they start off each morning in a kind of “productivity debt”, which they must struggle to pay off through the day, in hopes of reaching a zero balance by the time evening comes. Few things feel more basic to my experience of adulthood than this vague sense that I’m falling behind, and need to claw my way back up to some minimum standard of output. It’s as if I need to justify my existence, by staying “on top of things”, in order to stave off some ill-defined catastrophe that might otherwise come crashing down upon my head.

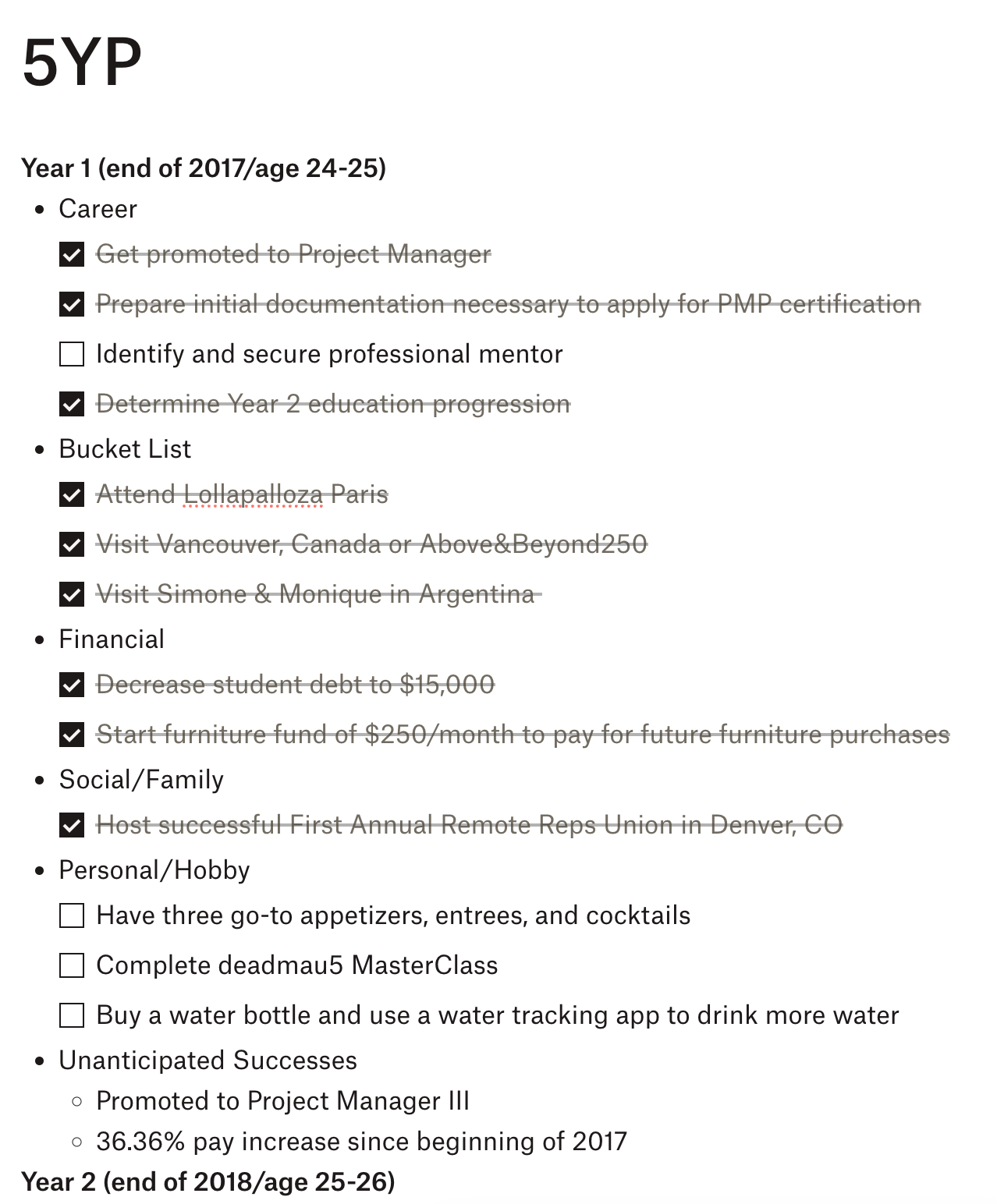

The feeling of productivity debt has plagued me for my entire adult life, and for most of my teenage years as well. When I was in my early 20s, this took the form of a five year plan, each year of which had individual goals that laddered up to a hypothetical future where I was finally “on top of things” (the same on top of things Burkeman is referring to in the title of his blog post).

If you knew me during this time in my life, you undoubtedly heard about these plans because I was borderline insistent that they were necessary to achieve personal and professional success. Actually, I’m fairly sure I went even further and said that it was outright irresponsible if you weren’t willing to take this sort of prescriptive approach to paying down your productivity debt (I didn’t use that phrase at the time), which I assumed everyone was accumulating, like me, just by existing.

My annual plans included a lot of the usual suspects (get a better job, make more money), but they also included things like being able to make three “go to” appetizers, entrees, and cocktails, reconnecting with an old friend every quarter, and tracking my water intake. I can’t tell you how many books I read (including the acknowledgements, of course) so that I could check the associated box. I got multiple Amazon Web Services (AWS) certifications and spent Christmas Day one year finishing the final project for Harvard’s CS50: Introduction to Computer Science course.

I didn’t necessarily feel strongly about doing any of these things (I don’t like cooking at all, let alone multiple courses)—I just felt like I had to. But after years of making these plans and tracking my successes and failures, I recognized that this obligatory process was not as motivating as I had expected it to be. Instead, it was just exhausting (I didn’t realize that the obligation was what made it exhausting until much later, however). No matter how few goals I set, I never achieved all of them (I still don’t know how to make a single appetizer).

Not only that, I always felt worse about the goals I didn’t achieve vs. the ones I did. Looking back at my old plans, many of the “unanticipated successes” I didn’t plan for (some of which were quite meaningful, like eliminating my student debt years earlier than expected) somehow still feel small in comparison to the unchecked boxes of very important goals I set but didn’t achieve, like reading a behavioral economics book every quarter.

By the time the pandemic reached New York City in 2020, I had given up on the annual process entirely. Like many of us during that time though, I still hoped to use lockdown to finally do some of the things I had been deferring until I was on top of everything. In my case, that was learning how to use Ableton. I’ll let you guess whether I know how to use Ableton today.

In 2021, I read Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, the central premise of which is that the feeling of needing to get so much done, of productivity debt, of feeling like you have to get on top of a bunch of things or reach the end of your to-do list before you truly start living your life, is related to humans being unwilling to accept the fact that we have just 4000 weeks (~76 years) to do all of the things we want to do. For almost all of us that means, no matter how hard we try, we will never be able to do everything that we want to do, so we might as well just start living now rather than trying to defer things like learning Ableton until some hypothetical future date when we’re finally on top of things (which will never come).

This made sense to me intellectually, but it felt a bit overly academic. And there was always the counter argument of “isn’t the fact that we’re finite even more of a reason to try to extract as much “value” from our time as possible?”

It wasn’t until I read “It’s worse than you think”, another post from Burkeman’s blog, titled The Imperfectionist, that this idea of finitude really sunk in:

We think of certain kinds of challenges as really hard when they are, in fact, completely impossible. And then we drive ourselves crazy trying to deal with them – thereby distracting and disempowering ourselves from tackling the really hard things that make life worth living.

A case in point: you feel overwhelmed by an extremely long to-do list. But it’s worse than you think! You think the problem is that you have a huge number of tasks to complete, and insufficient time, and that your only hope is to summon unprecedented reserves of self-discipline, manage your time incredibly well, and somehow power through. Whereas in fact the incoming supply of possible tasks is effectively infinite (and, indeed, your efforts to get through them actually generate more things to do). Getting on top of it all seems like it would be really hard. But it isn’t. It’s impossible.

It’s difficult to express just how hard that hit for me.

Adopting this mindset (which Burkeman calls Imperfectionism) didn’t cause the anxiety surrounding my own productivity debt to disappear entirely, but it did help significantly. I started living more flexibly. Instead of annual goals, I did The Annual Review from Steven Schlafman and Downshift, which I’ve recommended to even the most goal-averse of my friends and colleagues.

This all worked well enough for a few years. But then I decided to quit my job.

Once I decided to take a sabbatical, somewhat paradoxically, the productivity debt came roaring back. This was due to at least two reasons:

I had a tremendous amount of preparation I genuinely needed to do for the trips I was planning to take during this time

I felt like I needed to pack in all of the things I had been neglecting (self discovery, creative expression, my 500+ article reading backlog) into the fixed time window of my sabbatical

Without realizing it, I fell back into old habits and built a Notion database with 50+ sabbatical planning documents (does it count as progress if many of them are archived?). Some of these documents are purely logistical (accommodation and flight details, my overall budget), but many of them are in the same vein as my old annual plans. They’re infinite to-do lists.

So when the first cycle of my sabbatical (cycles being yet another planning mechanism that, at this point, I’m too embarrassed to even explain) didn’t go as I anticipated, unsurprisingly, my grand plans came crashing back down to reality. I was back in productivity debt, except now even more so because I didn’t have outputs from my job to temper my productivity anxiety.

Coincidentally, I had brought Burkeman’s latest book, Meditations for Mortals: Four Weeks to Embrace Your Limitations and Make Time for What Counts with me on my trip. Reading is one of the 100 things I have been neglecting and that I wanted to make up for during my sabbatical.

This book is effectively a collection of Burkeman’s blog posts and, fortunately for me, he starts the book with “It’s worse than you think.” Rereading the section above (and with years of subconscious processing), I realized I didn’t need more or better goals. Instead, I needed limits.

A few days later, I was listening to an article on a run about the fallacies of systems thinking, which is the idea that you can map out all the parts of a system and understand how they interact in order to predict and thus influence, if not outright dictate, outcomes. Systems thinking appeals to those of us who experience productivity debt because it suggests that even a system as complex as life can be understood, mapped, and controlled.

The point of the article, titled “Magical systems thinking” was to highlight exactly that line of thinking as incorrect:

Systems analysis works best under specific conditions: when the system is static; when you can dismantle and examine it closely; when it involves few moving parts rather than many; and when you can iterate fixes through multiple attempts. A faulty ship’s radar or a simple electronic circuit are ideal. Even a limited human element – with people’s capacity to pursue their own plans, resist change, form political blocs, and generally frustrate best-laid plans – makes things much harder. The four-part refrigerator supply chain, with the factory, warehouse, distributor and retailer all under the tight control of management, is about the upper limit of what can be understood. Beyond that, in the realm of societies, governments and economies, systems thinking becomes a liability, more likely to breed false confidence than real understanding.

This was “It’s worse than you think” phrased in the context of systems thinking, which reminded me of something I’d read years ago from John Cutler, who is a self described “systems (over) thinker.”

Cutler has written a lot about systems thinking, organizational and product development, but one thing that has consistently stood out to me is his writing on enabling constraints:

Recently I have started adding the idea of Enabling Constraints to the mix. Why? Teams often find too many floats to be paralyzing. Especially in conditions of uncertainty and complexity. They choose to create Enabling Constraints to help them make progress. Enabling Constraints enable, and Limiting Constraints limit.

Enabling constraints are focusers. They constrain (sometimes just temporarily) the set of acceptable choices and/or behaviors in order to make it easier for you to focus on the things that matter most to you.

I like this description of enabling constraints that John Cutler recently shared because it does a good job of explaining how the spirit of enabling constraints is fundamentally different from goals (or even anti-goals, which are just goals by another name):

Constraints aren’t magic. They’re agreements, habits, and cultural patterns that need care. They shape behavior only when people see the intent behind them and choose to engage with that intent.

…

Treat [constraints] like a practice that needs reinforcement, not a checkbox to tick. However, also be willing to set an expiration date for the experiment and agree to revisit it at a future point. Don’t treat things as too precious.

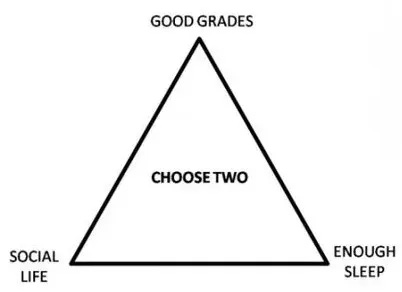

If the concept of enabling constraints still feels a bit too esoteric, maybe this meme which has been circulating at least since I was in college will make more sense:

“Choosing two” instead of trying to come up with some elaborate system to achieve all three is a form of an enabling constraint.

Here are some other examples of enabling constraints:

No meetings before 10AM or after 4PM - protect morning deep work time as well as prevent evening meetings from bleeding into your personal life

Only respond to emails during two pre-scheduled blocks each day - reduce email-induced context-switching while ensuring you’re still responsive (plus, quickly replying to emails just makes people more likely to email you)

Don’t purchase anything new for 30 days - discover what you actually need vs. what are just impulse buys; plus, if you do end up buying, you’ll treasure it even more

Only have one open browser tab at a time - finish what you’re reading or working on before moving to the next thing

Make time every morning to work out, write, or whatever you think is important before you do anything else - pay yourself first and remove the daily negotiation process about when/if to do this thing that you already know is important to you

John Cutler provides even more work related examples in this post

Enabling constraints feel like a way to actually practice Burkeman’s Imperfectionism. They’re more like guardrails than internal laws like ‘you must have an annual plan.’

Here’s my own list of enabling constraints that I’m currently trying to practice:

Reduce parallel threads far below what seems most efficient. You can’t do more than two things at a time and any attempt to exceed this cognitive limitation results in anxiety and burnout. Regardless, most activities are more enjoyable when they have your full attention.

Act before you feel ready. Start projects without perfect preparation. Make decisions without complete information. Learn by doing.

Accept imperfection in order to make progress. Your taste will often exceed your skill. Done today is better than perfect next week.

Share before you feel ready. Share rough artifacts and prototypes frequently. Ideas have limited value until they’re public. Your unique perspective and implementation matter even when the underlying idea isn’t novel.

Push yourself to bet on upside potential. Trying to minimize downside risk makes life smaller. Follow curiosity even when it seems unproductive; exploration and discovery are inherently inefficient.

Don’t even try to consume all the content. You can’t engage with everything that interests you. Make time for what matters most now and let the rest flow past guilt free.

Accept your physical needs even when they feel like compromises. Sleep, exercise, and nutrition can’t be deferred. If these languish, everything else degrades.

Accept that saying yes to one thing means saying no to others. Only say yes to things that clearly serve your priorities, then honor those commitments. This includes saying no to yourself.

Be willing to look incompetent. Other people have skills, perspectives, and knowledge you don’t, and they’re usually more than happy to help. Greatness is in the agency of others.

Design for who you actually are. You can’t force yourself to be a fundamentally different person. Accept your actual rhythms and preferences instead of chasing a hypothetical better version.

Accept finitude (it’s worse than you think). You won’t be able to do everything you want to. Choosing to do something with your limited time is what makes it meaningful.

To me, enabling constraints is about trying to do a few things as well as you possibly can, and letting the rest go, guilt-free.

I plan to write more about my attempts to incorporate enabling constraints into my life and work. And so, to do just that, I created Enabling Constraints.