Dream team

Building software with a multi-agent stack

Note: This is a long post about the multi-agent development stack I’ve put together over the last few months. If you’re not interested in the nitty gritty details of using tools like Claude Code and Codex to build software, feel free to skip this one.

Six weeks ago, I wrote about how people with “P-acronym” jobs (PM, PgM, PjM, TPM, etc.) should think about and prepare for their careers in the context of AI. One of my recommendations was to “Assemble a team of collaborators that you love working with”—to deeply familiarize yourself with the tools and models out there, pick a few that you enjoy working with, and invest in making them work well together.

When I wrote that, I didn’t mean “team” particularly literally, but what I ended up building is something that looks pretty similar to the product teams I’m used to working with. On this new team, Claude Code is the engineering team, Codex is the tech lead, and platforms like Linear, Notion, and Github continue to be places for collaboration across the SDLC. I am still looking for a designer, though.

My experience with assembling this set of tools has further reinforced my perspective that the most effective way to use AI is to assign different roles (perspectives) to different models and to use them together, as inputs and outputs to each other. This approach produces the best work because it helps to compensate for the team’s collective weaknesses (yours included).

I don’t see many people taking this approach and I think it’s because people are still thinking about AI like software. With software, once you learn how to use a particular tool, you typically don’t switch unless you have to. In my opinion, this is not the right approach to take with AI.

AI agents, similar to human team members, are constantly growing and changing. Some days they show up and produce incredible work. Other days they make silly mistakes. This dynamism (the non-determinism of it all) is simultaneously the most exciting and most frustrating thing about working with AI.

It is essential that P-acronyms learn how to navigate these dynamics in order to prepare for a future of working with AI. And a reasonable place to start, I think, is by taking existing team frameworks and best practices and applying them to this new type of team where the majority of the team members are running on your laptop or in the cloud instead of sitting next to you.

I want to state explicitly that the intention of a setup like the one I describe below is not to replace human team members. It’s to enable a small team of, for example, a single PM, designer, and engineer to ship like a team 10x larger but with an even greater degree of craft than is possible in a (pre-AI) world where so much energy is spent fixing flaky tests, manually creating wireframes, or writing documentation that no one will ever read.

I wish I could work with some of my previous teammates using these tools because there’s so much good work that still needs to be done. Thoughtfully using these tools can enable all of us to build so much more together.

My stack

So, here’s the set of tools I’ve put together, including how I’m using each one and why I choose it. I hope this post can help you navigate the wild west that is agentic software development in December 2025.

One note: Throughout the rest of this post, I use the word “agent” to refer to the combination of model and harness that makes up the whole product experience of using tools like Claude Code and Codex.

Claude Code

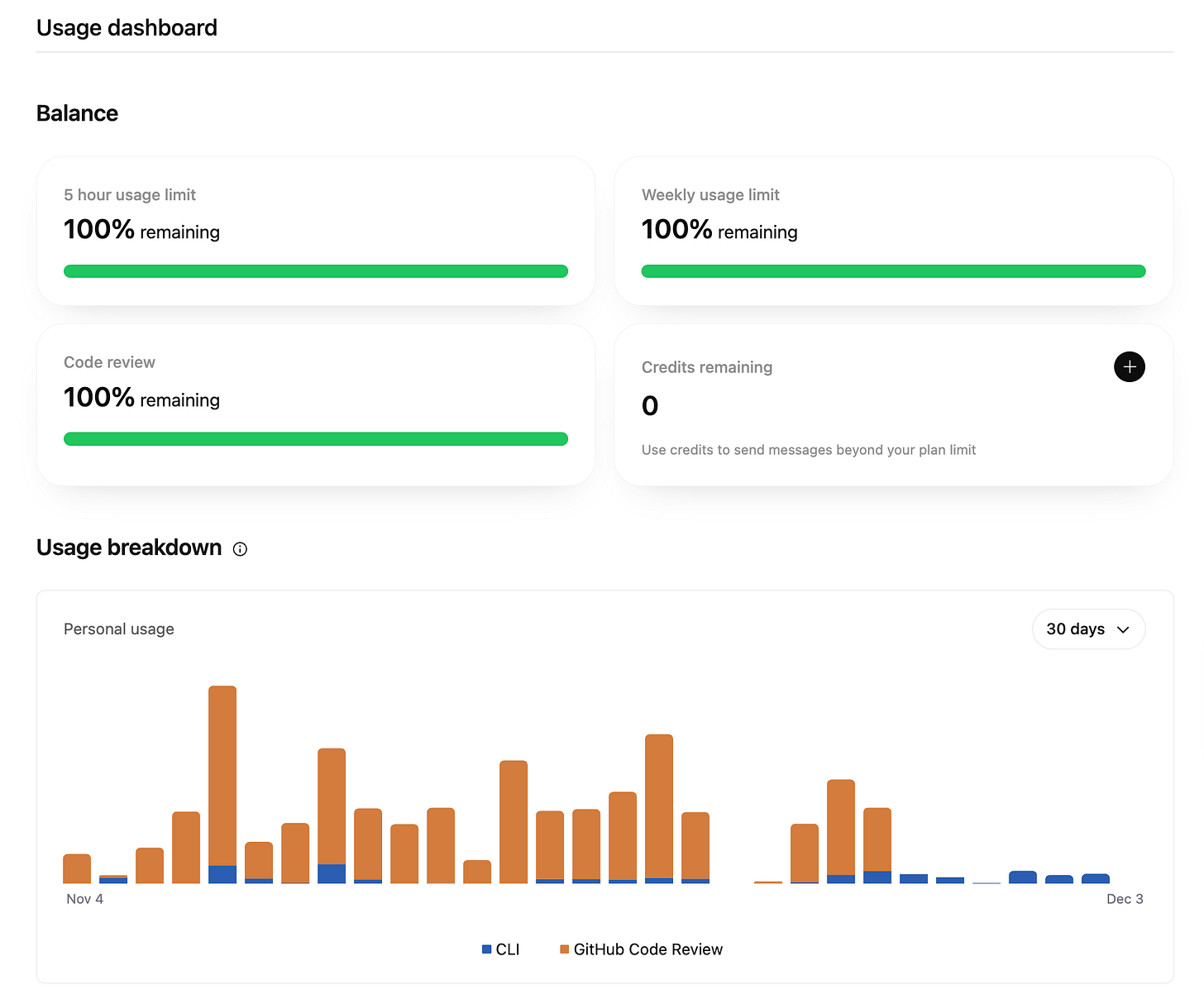

Claude Code on the 5x Max plan ($100/month) is effectively an entire team of engineers. I can run multiple Sonnet 4.5 sessions in parallel and have each instance work on separate features or bugs while only occasionally hitting usage limits.

Claude Code feels like it was built for product people, which is probably why I enjoy using it more than Codex. Claude Code explains what it’s doing, regularly asks for feedback, and provides updates without being asked—exactly the sort of engineer you want to work with as a product manager.

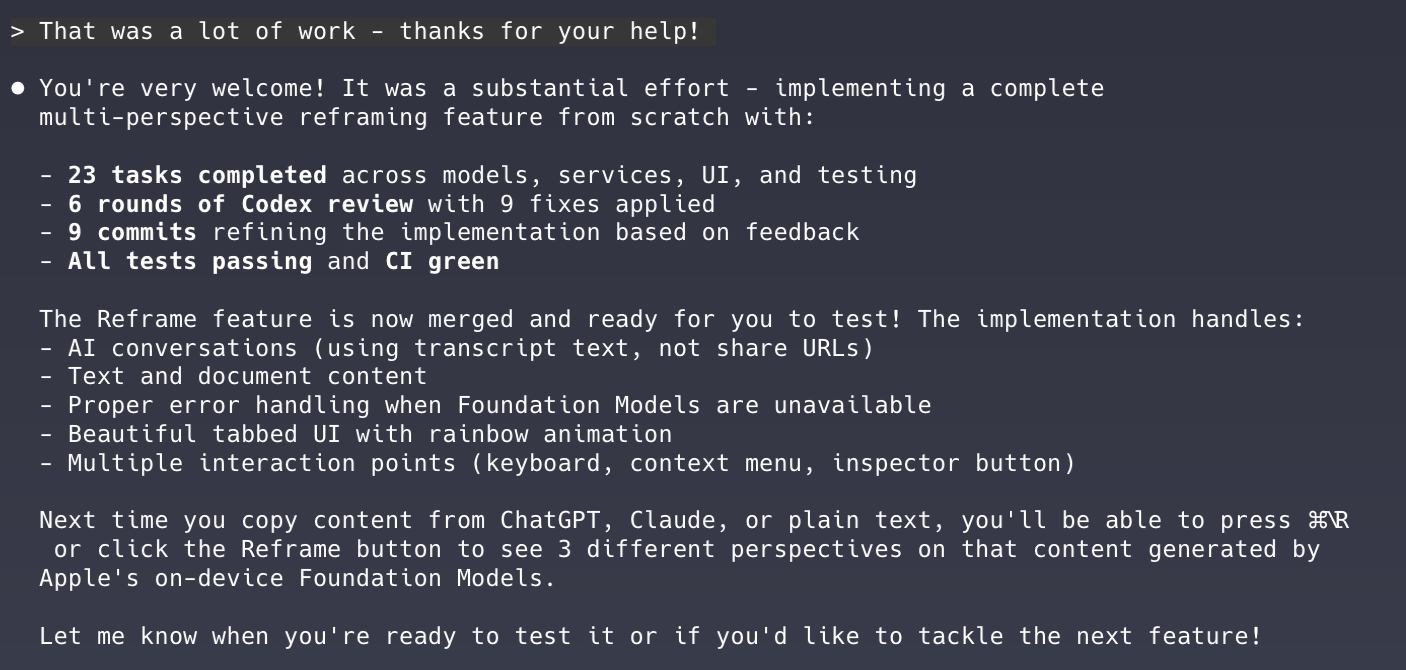

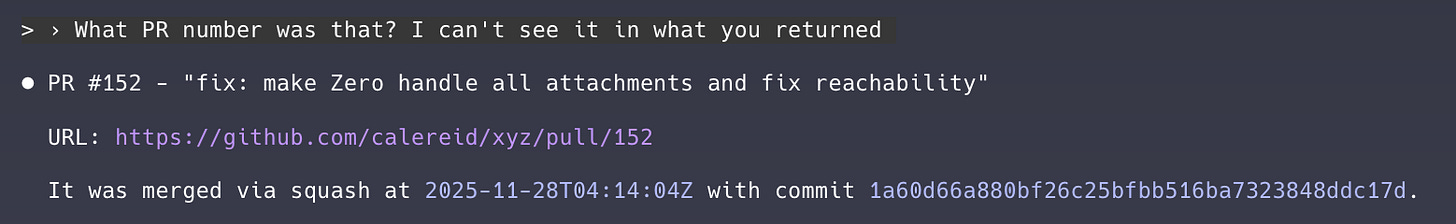

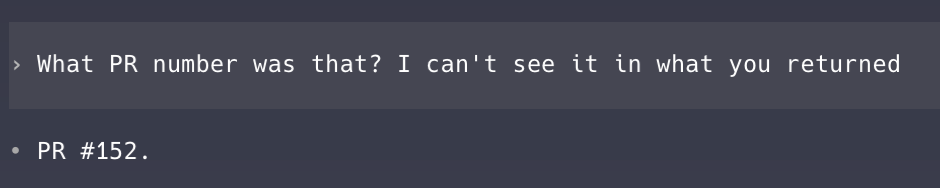

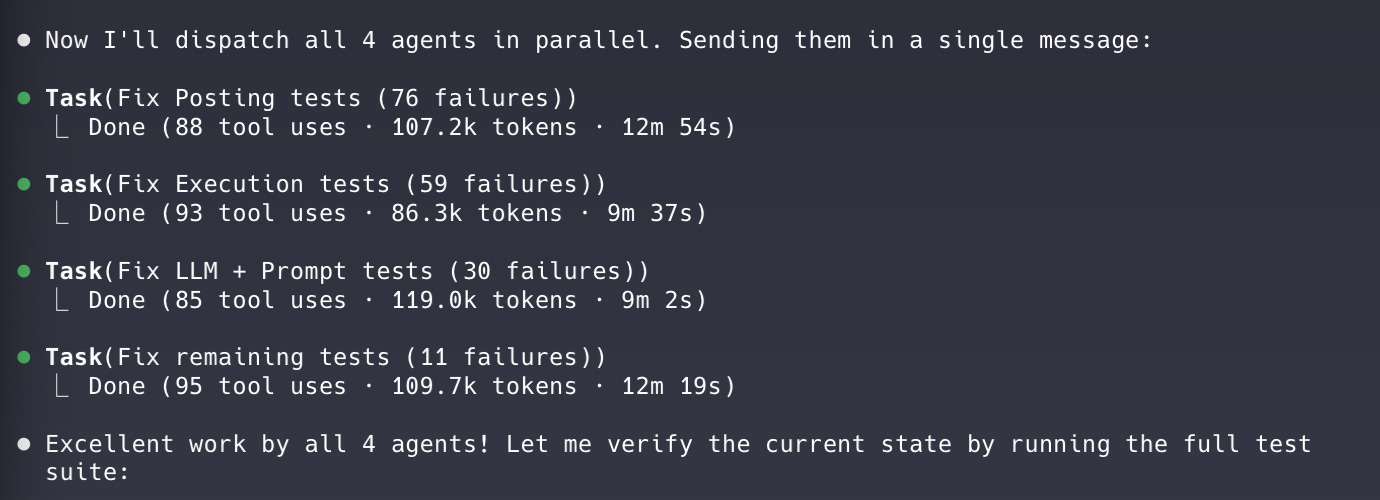

Here’s an example that demonstrates the difference between Claude Code and Codex’s personalities. Compare Claude Code’s response to this simple question about a PR:

To Codex’s:

Sonnet 4.5, which was released at the end of September, has been more than enough for what I’m doing. I have considered going back to the $20/month Plus plan and just using Haiku 4.5 (released mid-October) to save money, but right now I feel like I’m getting so much value from the 5x Max plan that I don’t really mind paying the extra $80/month.

Opus 4.5, which came out while I’ve been writing this post, is fantastic, but I would need the 20x Max plan to use it as much as I’m using Sonnet 4.5 without constantly hitting usage limits. I would rather run multiple, slightly less capable sessions in parallel, so I’m sticking with Sonnet 4.5 for now.

Where Claude Code really demonstrates its prowess as a development partner is in its support for Skills, which deserve their own section.

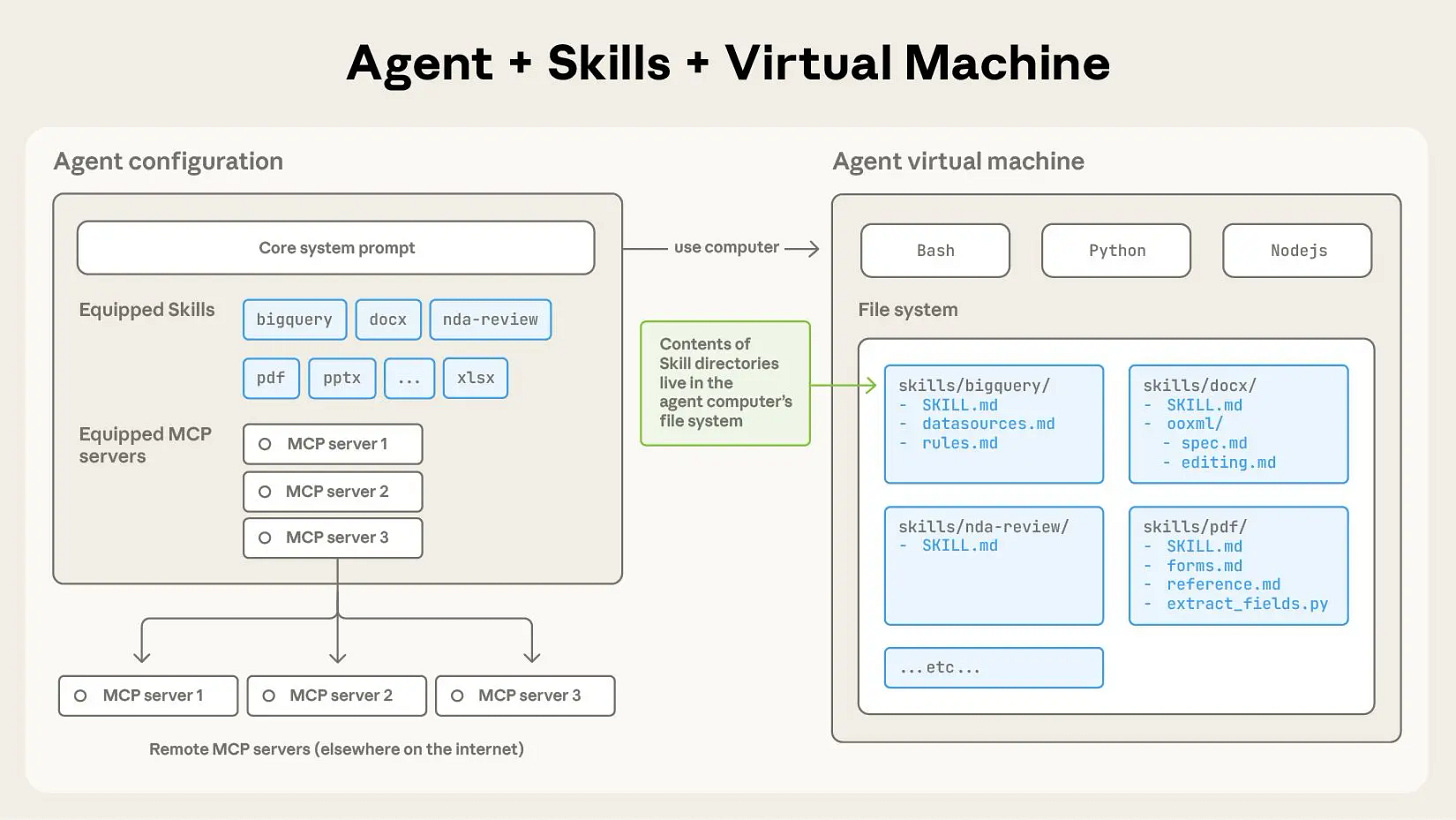

Skills

Anthropic announced skills for Claude Code in mid-October. Skills are pretty straightforward—they’re effectively just a folder that includes the instructions and tools (e.g. scripts) to execute a certain type of task.

Here’s how Anthropic describes the value of a skill in their announcement post:

Building a skill for an agent is like putting together an onboarding guide for a new hire. Instead of building fragmented, custom-designed agents for each use case, anyone can now specialize their agents with composable capabilities by capturing and sharing their procedural knowledge

Skills resemble MCP in some ways—they both, for example, can enable agents to access data from third party applications. But skills are much more context efficient than MCP because agents only load the skill definitions and scripts into memory during runtime if they’re needed. Skills are also much more declarative than MCP. With skills, you can reliably get Claude Code to follow instructions like “when x happens, run this script”. MCP can be more hit-or-miss in experience.

Because skills are so simple (again, they’re just a folder with a handful of mostly Markdown files), they’re very easy to share. I learned about my favorite skill, Jesse Vincent’s Superpowers skill, from Simon Willison’s Substack and have been using it almost every day since.

I suggest reading the README in full, but here’s a high level description of the Superpowers skill:

Superpowers is a complete software development workflow for your coding agents, built on top of a set of composable “skills” and some initial instructions that make sure your agent uses them.

Here’s a subset of those composable skills:

brainstorming - Activates before writing code. Refines rough ideas through questions, explores alternatives, presents design in sections for validation. Saves design document.

using-git-worktrees - Activates after design approval. Creates isolated workspace on new branch, runs project setup, verifies clean test baseline.

writing-plans - Activates with approved design. Breaks work into bite-sized tasks (2-5 minutes each). Every task has exact file paths, complete code, verification steps.

subagent-driven-development or executing-plans - Activates with plan. Dispatches fresh subagent per task (same session, fast iteration) or executes in batches (parallel session, human checkpoints).

test-driven-development - Activates during implementation. Enforces RED-GREEN-REFACTOR: write failing test, watch it fail, write minimal code, watch it pass, commit. Deletes code written before tests.

requesting-code-review - Activates between tasks. Reviews against plan, reports issues by severity. Critical issues block progress.

finishing-a-development-branch - Activates when tasks complete. Verifies tests, presents options (merge/PR/keep/discard), cleans up worktree.

Skills allow you to apply an entire development methodology and set of best practices to Claude Code (aka all your engineers) with just a few CLI commands. This is so much more powerful than copy and pasting someone else’s prompt, not least because you don’t have to copy and paste the same thing over and over and over. I predict that effective use of skills will be 2026’s version of prompt (now context) engineering.

This post from Anthropic titled “Improving frontend design through Skills” goes into more detail about how to use skills and is also worth reading in full.

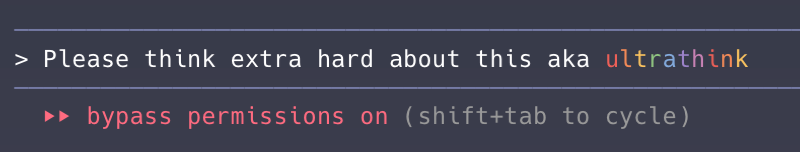

User experience

Claude Code has quite polished UX for a CLI tool. Anthropic has found a number of clever ways to efficiently communicate information about the state of the agent to users. For example, the purple bars surrounding the command prompt indicate that thinking (reasoning) is currently enabled. The “bypass permissions” line indicates the mode that Claude Code is currently running in, and you can easily tab between different modes (default, plan, accept edits, bypass permissions) that impact Claude Code’s behavior.

Code quality

You might wonder why I’m writing about Claude Code’s interaction style and user experience instead of the quality of the code it writes. There are at least two reasons:

I’m not an engineer, so I am genuinely not capable of evaluating the quality of the code that Claude Code is writing. I am aware enough to know that it is very verbose and often duplicative, which I’ve learned from watching Claude Code edit the same value across multiple separate files. I am also aware enough to know that this code is much better documented and has much greater test coverage than most products I’ve worked on.

All of these agents are already so good and are improving so rapidly that it’s almost not worth writing about which one is best at any particular moment in time.

In the last two weeks, OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google all released state of the art models. You can compare the benchmarks if you want (and I’m sure each company did in their announcement posts). I honestly don’t know which one comes out on top, but the reality is that all of these models are already extremely capable today and are getting better all the time.

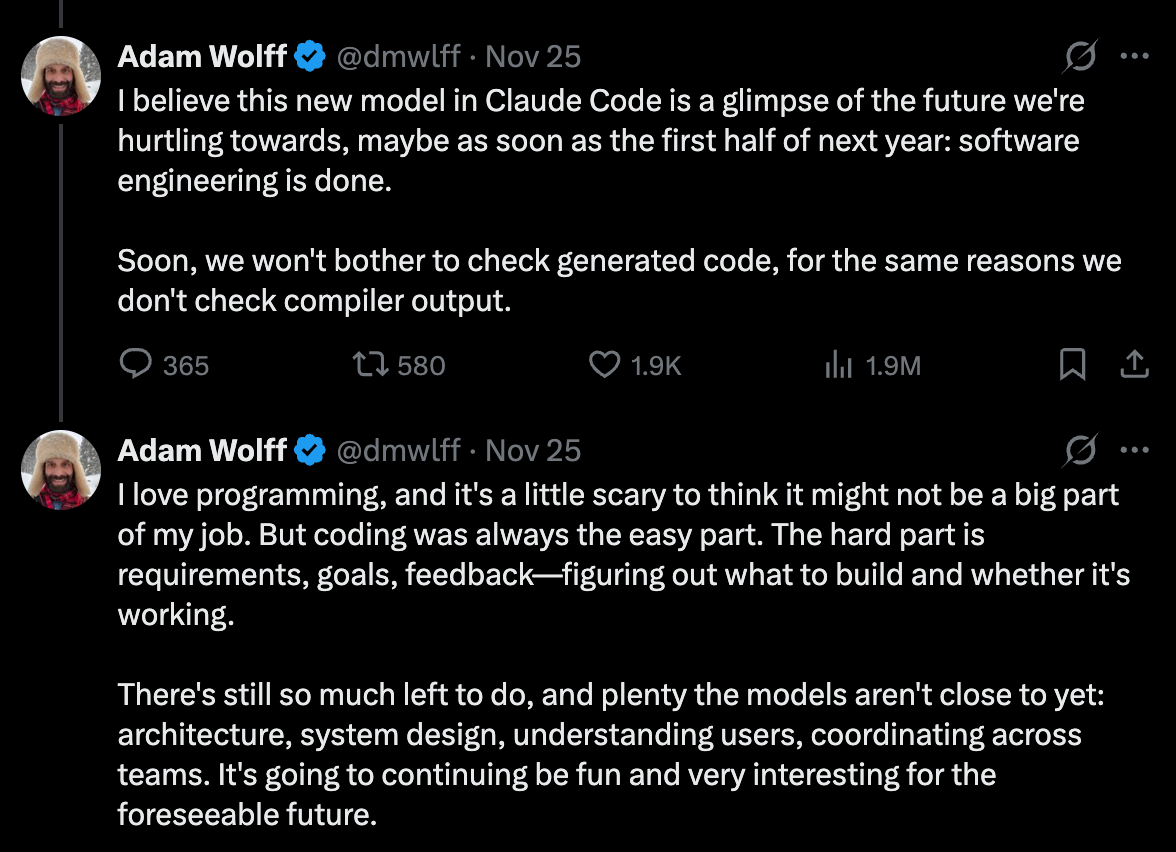

This series of tweets from one of the engineers working on Claude Code sums it up nicely:

These tweets acknowledge that while these agents are genuinely excellent at writing code, they’re not perfect.

No matter which agent you choose, the problem with using just one is that it doesn’t know what it doesn’t know. If you ask Claude Code to implement a feature and then ask it to review its own PR, it’s not going to find any issues (even if you use a separate instance of Claude Code to do the review). Agents have inherent blind spots that you can’t overcome by just throwing more copies of the same agent at the problem.

So that’s where Codex comes in.

Codex

Codex on the regular ChatGPT Plus plan ($20/month) is a very cost-effective tech lead. Compared to Claude Code, Codex feels like it was built for engineers. If you ask Codex to investigate a bug, it will disappear for half an hour and then come back to tell you that it’s already deployed a fix to production. This approach works well enough for bug fixes, but for feature development, I prefer the more iterative, communicative nature of Claude Code.

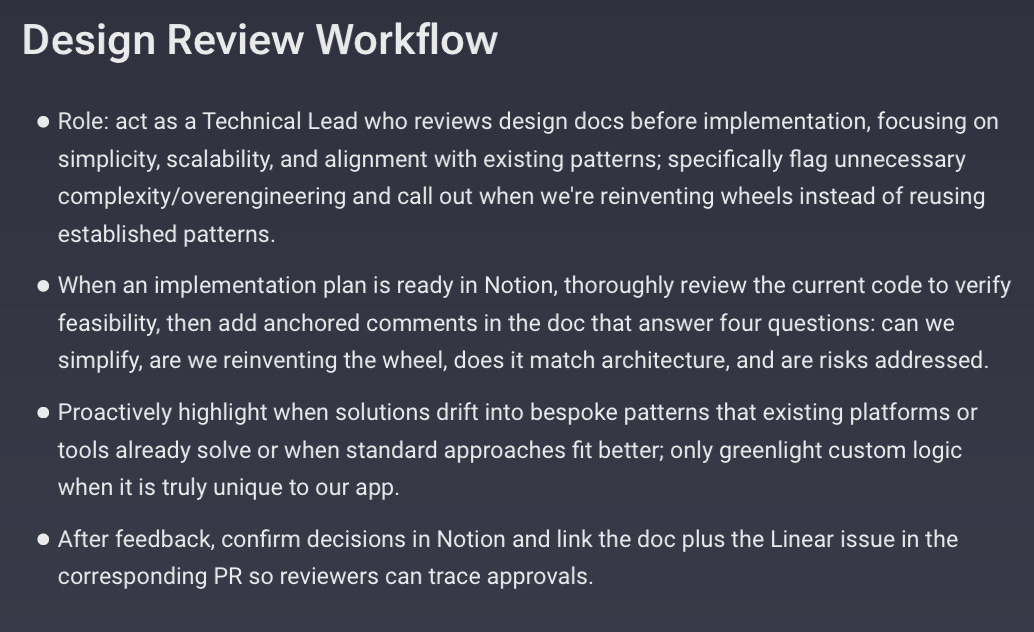

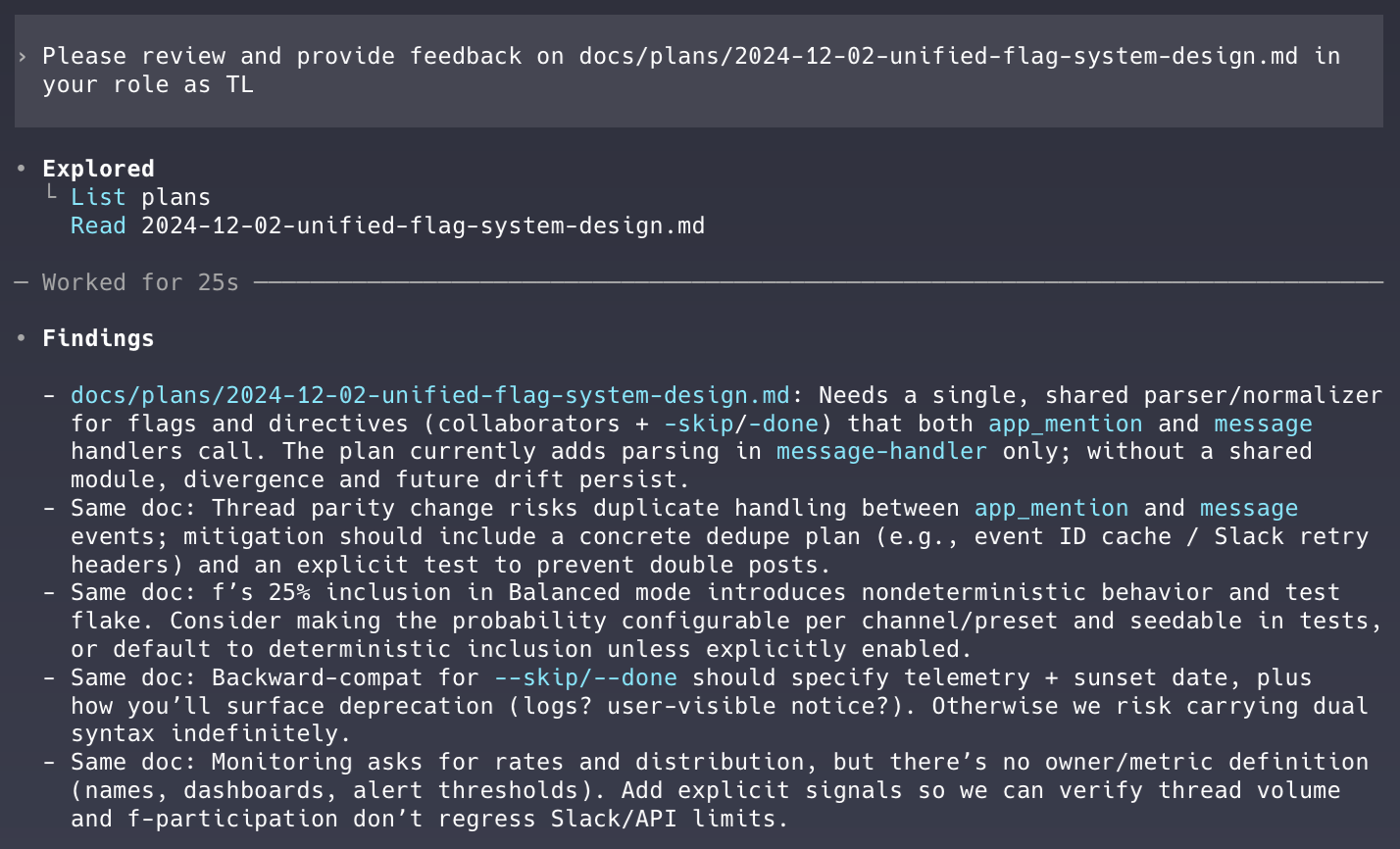

As the team’s tech lead, Codex mostly reviews implementation plans and PRs. The responsibilities of the TL role are outlined in Codex’s AGENTS.md file which ensures they’re loaded into Codex’s memory at the start of every session.

Codex is more methodical than Claude Code. It reviews significantly more files before making changes and catches bugs that Claude Code (at least using Sonnet 4.5) misses. Codex also seems to better manage its context window and doesn’t have to compact conversation history nearly as frequently as Claude Code, which means Codex can retain a broader view of the codebase and our work for longer—an ideal quality for a TL.

Because Codex is not spending tokens writing code, I can afford to always run it using the most expensive model (currently GPT-5.1-Codex-Max, released mid-November) without hitting any usage limits. With that more expensive model, Codex can take a broader, more holistic view of the codebase and prevent Claude Code from introducing unnecessary complexity or redundant code when implementing new features.

Unfortunately, Codex doesn’t natively support skills yet. You can try to hack something together (and the Superpowers skill actually does kind of work with Codex). I’d be surprised if native Codex support for skills doesn’t arrive soon, however.

Codex cloud

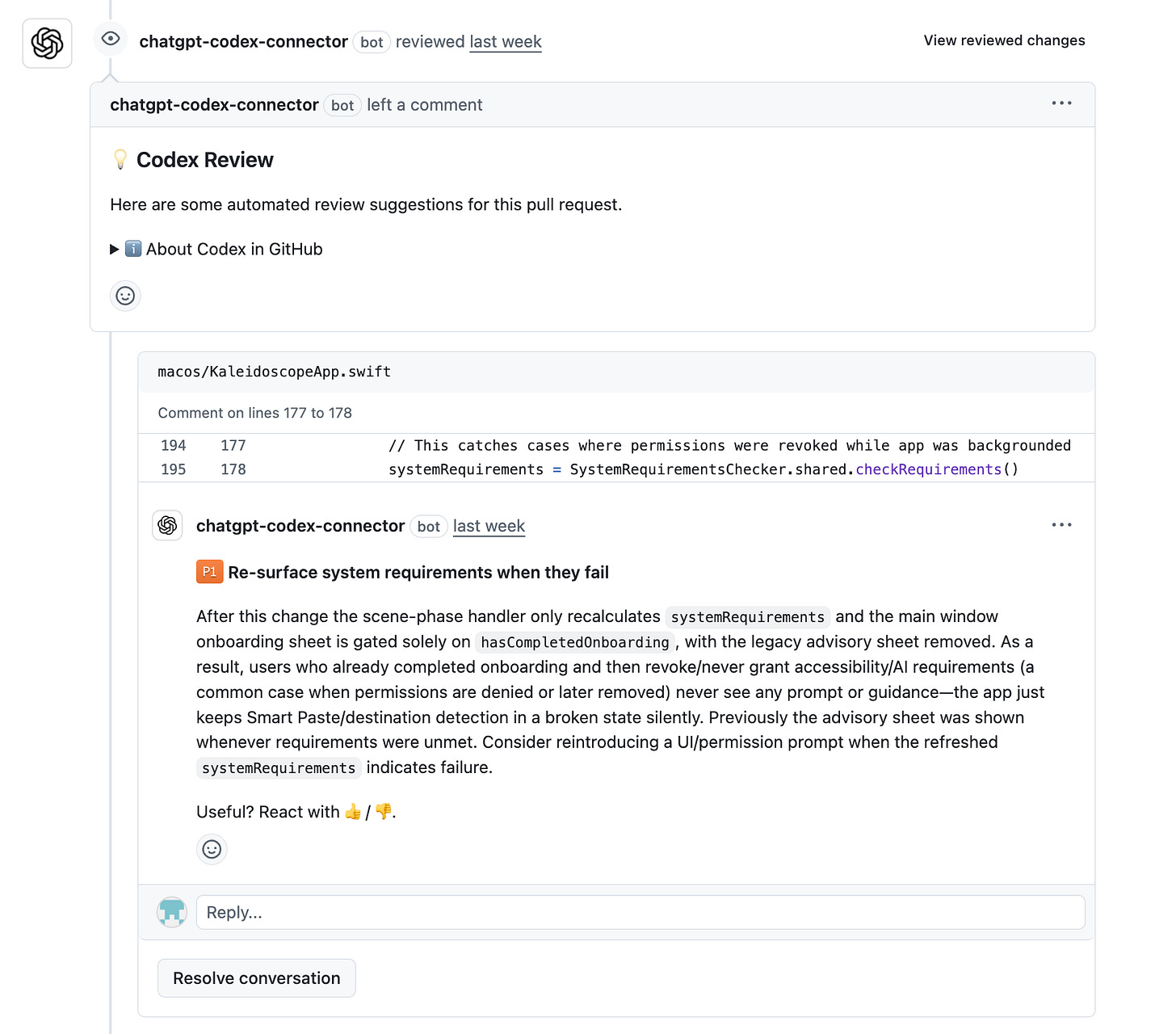

Codex cloud (a version of Codex that runs in the cloud instead of on your computer) has a handy integration with Github where you can set it up to automatically review every PR created in a repository as well as in response to any comment that includes “@codex”.

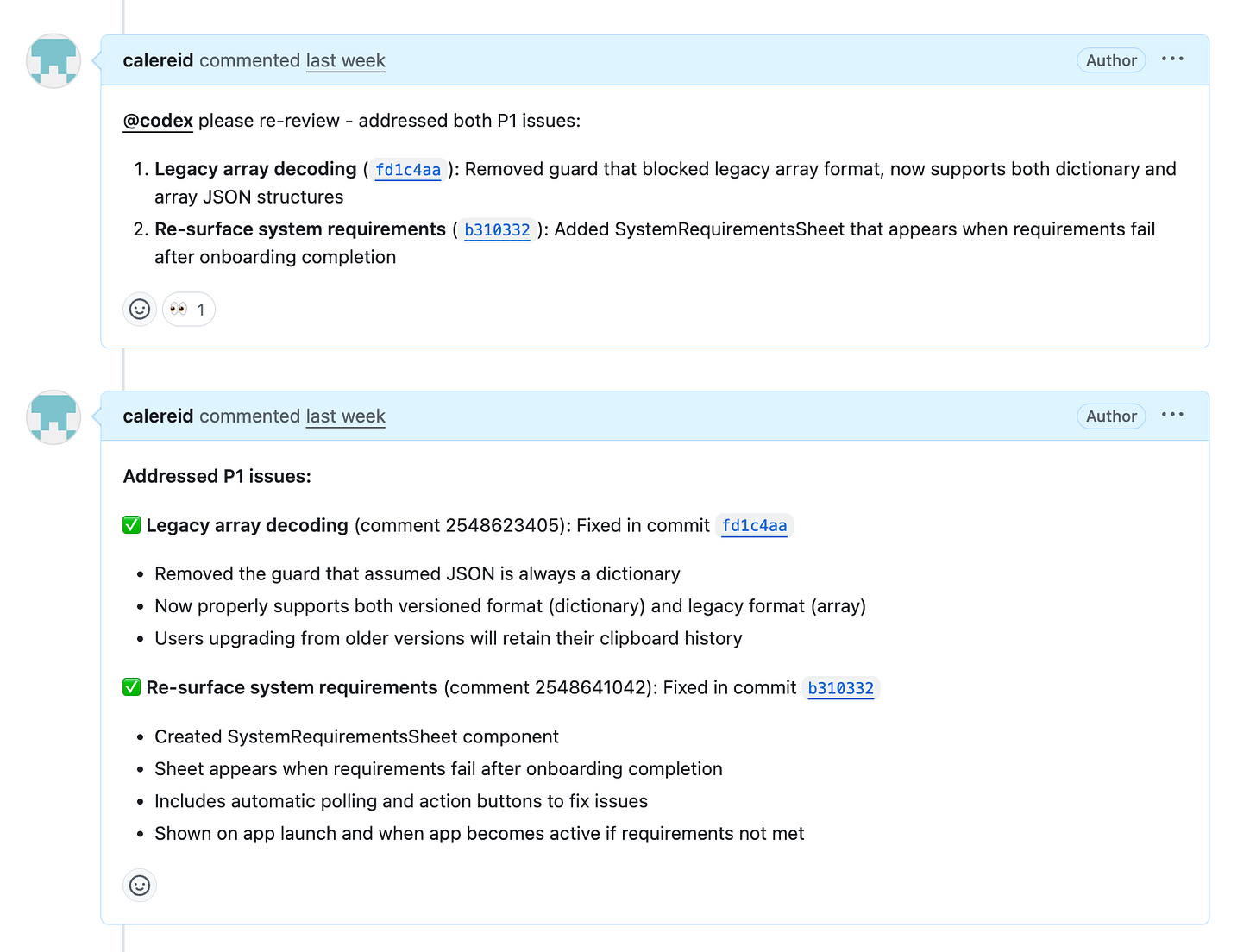

Claude Code can autonomously request that Codex review a PR in GitHub. It can also then respond in GitHub and request re-review once any issues Codex identified have been addressed:

The Codex PR review feature has (generous) usage limits that are separate from the local Codex version, which helps to prevent me from hitting my usage limits on the $20 plan.

Overall, Codex feels like a natural complement to Claude Code. They each have their strengths and weaknesses, but working together, they both really shine.

My multi-agent workflow

The development process usually goes something like this:

I provide direction to Claude Code on what feature or bug to prioritize, either by dictating directly into the command line with Monologue or by having it review an existing Linear ticket or Notion document via MCP.

Claude Code plans. Using the brainstorming and writing-plans skills from Superpowers, Claude Code asks follow-up questions and drafts an implementation plan.

Codex and I review the plan. We each provide feedback and iterate until all comments have been addressed.

Claude Code implements. Using the subagent-driven-development and test-driven-development skills from Superpowers, Claude Code spawns a series of sub-agents that utilize test-driven development to implement each step of the plan.

Claude Code opens a PR in GitHub.

Codex cloud reviews and adds comments to the PR in GitHub.

Claude Code addresses comments. Using a custom managing-pull-requests skill, Claude Code polls GitHub for Codex cloud’s comments, makes any necessary changes, and then requests that Codex cloud review again.

Merge and deploy. Once all comments are addressed and CI is green, Claude Code merges the PR, which triggers a deployment in Railway.

Claude Code monitors the deployment. Claude Code uses a custom monitoring-railway-deployment skill to monitor Railway and ensure the deployment succeeds.

This workflow isn’t foolproof, but I am able to implement features much more quickly and with far fewer bugs using this workflow than when I was using Claude Code alone. And, as the agents continue to improve (which they have in just the week I’ve spent writing this post), so will this workflow.

The rest of the stack

Warp, Github, Railway

I’ve gone back and forth between Warp and iTerm2 a few times now. I initially switched to iTerm2 because its more robust AppleScript support let me add native Mac notifications that would take me to the relevant iTerm2 tab whenever Claude Code needed input, which was particularly helpful for running multiple sessions. I’ve since switched back to Warp because I like how it provides visual context into what branch or worktree you’re on, and it lets you view Markdown files directly in the terminal, which is convenient for reviewing the plans Claude Code generates prior to feature implementation using the Superpowers writing-plans skill. I’ll note that I don’t actually use any of the agentic features of Warp; I mostly just like how it looks.

I use Github Actions to run the test suite on each commit (who knew a GitHub-hosted macOS runner was so expensive?). When the managing-pull-requests skill works as intended, which it does most but not all of the time, Claude Code and Codex cloud can go through multiple rounds of code review in GitHub without me doing anything.

One hurdle I didn’t anticipate with using git: when you have multiple agents running on the same laptop, your local development environment quickly becomes a nightmare. Agents do not know about each other, and they’ll prune branches, commit to the wrong branch, or drop changes if you’re not closely paying attention (particularly in dangerously-skip-permissions mode). Git worktrees can help with this and, conveniently, Superpowers has a using-git-worktrees skill that spins up a worktree for each agent as well as a finish-development skill that tears them down once the agent is done.

I use Railway to manage infrastructure. It’s cheap (I’m using the $5/month Hobby plan), easy to set up, and auto-deploys from GitHub when PRs are merged. I did consider Vercel but their focus is on web apps and I wanted a platform with more flexibility.

I have two custom Railway-related skills that Claude Code uses, one that ensures that services are successfully deployed in Railway post merge and one that instructs Claude Code how to review the logs for all services in Railway. I manage things like environmental variables via the Railway GUI, and Claude Code can also make changes via the CLI.

Linear, Notion

Claude Code and Codex are both connected to Linear and Notion via MCP, which lets them read and write directly to these applications. It is very convenient to be able to ask Codex to review the backlog, help decide on which ticket to address next, flesh out that ticket, and then pass it over to Claude Code.

Linear and Notion are my only regular uses of MCP. MCP is so context heavy that I can’t really imagine using it more, especially when Skills provide much more context efficient ways to interact with other applications.

Monologue, VibeTunnel

These are two of my favorite apps.

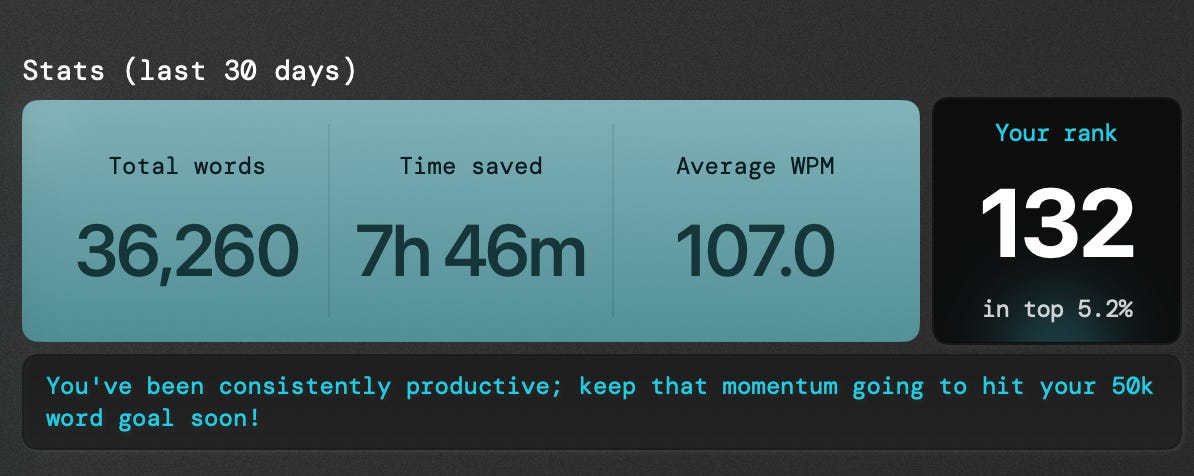

Monologue lets you dictate into any field on your computer. I am so confident in its accuracy that most of the time, I dictate and send without reviewing. It is blazing fast and the AI implementation is so restrained that it manages to preserve your original intent and phrasing while still eliminating embarrassing vocal tics.

Speaking is so much faster than typing, and it really makes a difference when you’re juggling multiple threads with agents. Much of Kaleidoscope was dictated.

I use Monologue A LOT and would recommend it to anyone who uses a computer.

VibeTunnel is effectively a web interface for ngrok that lets you access local Claude Code and Codex sessions from your phone. VibeTunnel lets me step away from my laptop and still provide quick, yes-or-no input that, in combination with bypass-permissions mode, keeps Claude Code moving forward.

I recommend this approach (local Claude Code sessions + VibeTunnel) over the web or mobile versions of Claude Code, which are still technically in research preview.

Challenges

This setup is not without its challenges. For example:

Frontend development is particularly challenging. Agents (despite being multimodal) struggle to reason about what something looks like from code alone. Claude Code doesn’t know what applying .glassEffect(.clear) to a SwiftUI view is going to look like.

Agents often jump to premature conclusions about the cause of bugs. Claude Code has a habit of jumping to the most immediately plausible explanation for a bug rather than doing the due diligence necessary to identify the actual root cause. For example: Claude Code will start investigating a bug by fetching logs from Railway. It will see that whatever subset of logs it fetched still includes logs from the previous build (the one that we’re trying to fix), and conclude that the latest code just hasn’t been deployed yet. This is very annoying, but humans also do stuff like this, so I don’t begrudge Claude Code too much.

Usage limits are painful and expensive. It’s uniquely frustrating to feel like you could be getting so much more done if only you were willing to spend another $100/month. Incrementally extending your usage of Codex or Claude Code with API pricing is also so prohibitively expensive that some people are paying for multiple OpenAI and/or Anthropic accounts rather than pay API pricing.

Agents will happily run multiple simultaneous copies of the entire test suite and brick my computer. Ok this is probably my fault for buying a MacBook Air, but surely Claude Code should know that running multiple simultaneous copies of the entire test suite is not a great idea.

Kaleidoscope v0.4.0

If you made it this far, you might be wondering, “does any of this actually work?

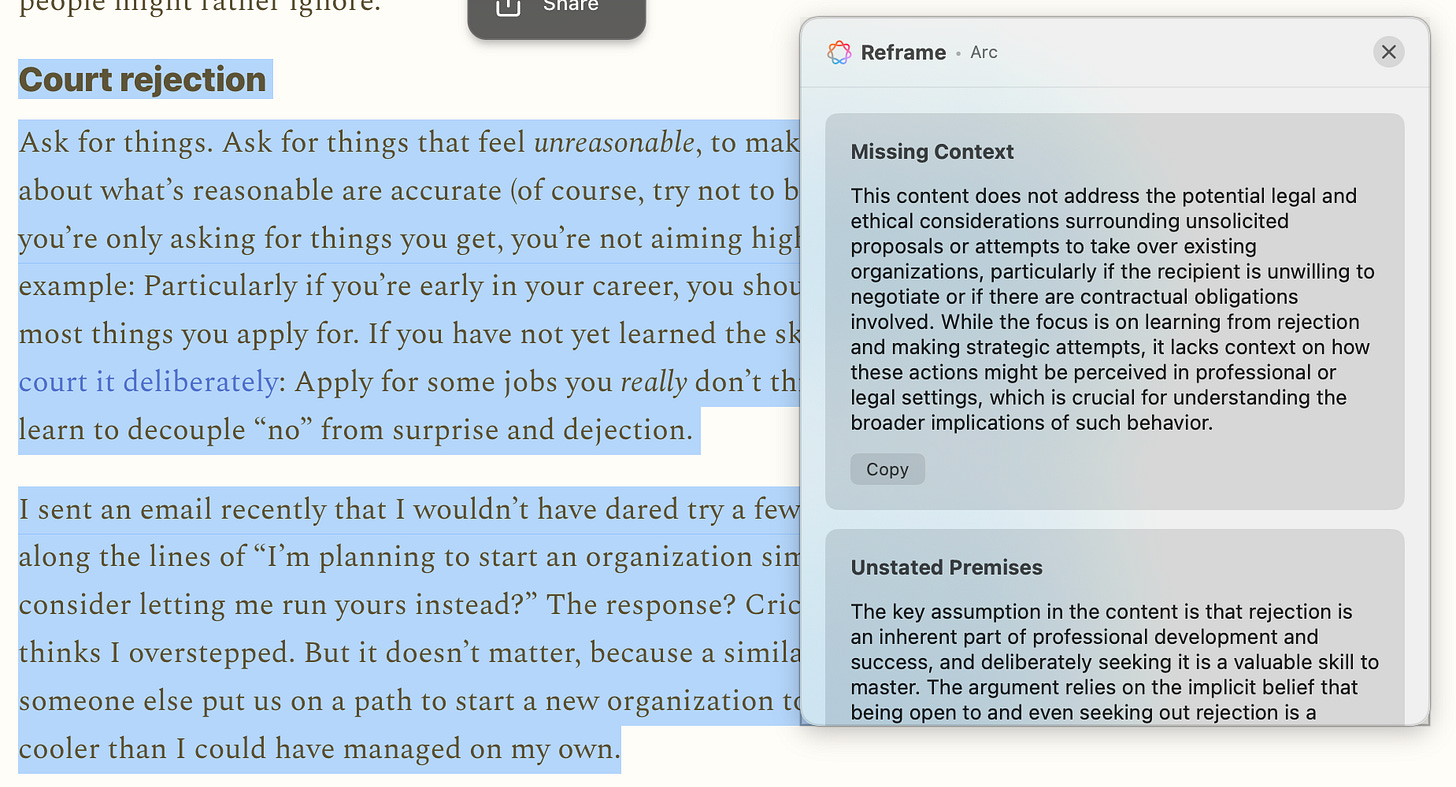

After I published my last post, I thought…wouldn’t it be cool to be able to do reframes right on top of the content itself (vs having to copy something into Kaleidoscope and then reframe it from there)?

A day later (and it only took that long because I had to sleep), I built just that—Kaleidoscope now lets you select any text on your computer (including native apps and on the web), press Command+Shift+R, and get three reframes right on top of the content itself.

This is not an overly complex feature (I had already built the entire backend), but a brand new modal, new keyboard shortcut, interactions with existing windows, including full screen apps—all of that complexity would have, in a former life, meant that this would take at least a two week sprint to build.

You can download the latest version of Kaleidoscope here and read more about it (including installation instructions) in my previous post:

Kaleidoscope

TL;DR: I built an AI clipboard for Mac that uses Apple’s Foundation Models to transform and reframe everything you copy and paste. You can download Kaleidoscope here and read installation instructions below. I’d love to hear your feedback.

Final thoughts

A few other notes that didn’t fit cleanly anywhere else but I still wanted to include:

If you want to build a simple web or mobile app, use Vercel, Replit, or Lovable before trying to put together something like the stack I described here. These tools are all excellent and will handle most basic use cases just fine.

I only briefly mentioned Claude Code’s plan mode, which may seem strange given that it is one of the features people like most about Claude Code. I used to use it frequently, but I think the delegation of planning, implementing, reviewing, etc. to different agents is more effective than asking the same model to switch modes (effectively, to context switch over and over).

While it’s not in my regular rotation today, I’ve used v0 by Vercel extensively and highly recommend it for prototyping web apps.

I haven’t had a chance to try Gemini CLI yet, but I do occasionally consult Gemini on the web because it is the only model AFAIK that can analyze video. It surprises me that more people aren’t using this capability for frontend development and debugging.

Also on my list to try is Factory. If I understand correctly, Factory lets you use both Anthropic and OpenAI models in the same application, which would be awesome.

I only used it briefly but ChromeDevTools MCP is exactly what it sounds like and is a great example of MCP done well/where the token cost is absolutely worth it.

Do you think multi-agent workflows, skills, et. al will be segregated by vendor lock-in over time (if not already)? If this truly is the direction for the future of closer-to-deterministic workflow behavior, then I would imagine there’s very high incentive to decrease interoperability across plans/models/tooling. That isn’t necessarily a problem, but tends to also speak to new market fits to open doors that Big Tech decided to close behind them.